The shortage of affordable housing has long been a concern of local governments. Recently, it gained the attention of state officials. The time seems right for action. But what action?

Therein lies the rub. Everyone seems to have a solution. Ideas abound. Seldom does one lower the price of a two-by-four, the value of land, or the hourly cost of employing skilled labor.

But wait. While solutions may not lower actual costs of materials and labor, they might lower the length of holding period before returns on such investments show a reasonable profit. They may lower the amounts of materials and labor required to achieve the end result. They might offer some innovative approaches. It deserves a look.

Some ideas claim that regulations stifle the provision of affordable housing. Certainly, room for reflection and revision exists. But do our cities really want to return to the days when more affordable housing was available, but oversight was minimal? Some folks still remember the stench of outdoor toilets in August. They also remember the rash of fires each December when holiday decorations overpowered electrical outlets.

Zoning has the privilege of being a modern target. Just eliminate single-family zoning districts, some say. The problem will resolve itself. Developers will suddenly stop meeting the market demand for single-family homes and start building apartments. It is certainly comforting to think so.

Current ideas assume that the problems are uniform across the spectrum of cities. Therefore, solutions should be as well. Is that an oversimplification? Maybe. Consider our state. We could divide the need for housing into at least three categories.

For one, growth is rampant and so is the need is for workforce housing. This brings planners into conflict with the troublesome supply and demand curve. This is a chart with prices on the vertical axis and quantities on the horizontal axis. Where they intersect indicates the price of a commodity.

When the demand exceeds the supply, prices rise. When the supply exceeds the demand, prices fall. But how far do they fall? With housing, the price of a house may fall to a point that improves marketability. It may or may not fall to a point that means affordability for service workers. Developers in these cities encounter trouble meeting demand, much less creating a surplus.

These are cities that might benefit from regulatory reform.

In another division, cities that are healthy, but growth rates remain low or moderate. Here the need is for a stable housing market. There is a demand for enough new housing units to replace obsolete ones or ones destroyed by disasters.

These are cities that need protection from blighting influences that might threaten stability. Infill development should satisfy demand for new housing.

For a vast number of our municipalities, the need is simply for housing that is decent, safe and sanitary. There will be no gated communities built within their boundaries. No subdivisions claim protection by restrictive covenants. Our fellow citizens freeze in Arkansas winters and suffer during our summers in structures that are not fit for human habitation.

These are cities in which the private sector alone will not solve housing problems.

Unfortunately, legislation seldom, if ever, recognizes such differences in cities. Laws are unitary, but demand for housing is not a uniform concept. Some areas cannot meet the demand for housing. Some areas have seen few new homes in years, some none.

Consequently, we see that the issue of housing affordability is complex. As such, the requirement for a complicated and incremental approach asserts itself. Let us look at some current ideas. Some are in place, some are contemplated, and some are wishful.

Accessory dwelling units in all residential zones can add to the supply of housing at reduced costs. A new law in our state mandates this, and we look forward to documenting the results.

There are also experiments in outlawing single-family-only districts in zoning codes. This could have the effect of “NIMBY-proofing” the development of multi-family developments that could then be built “by-right.” All zoning codes now allow for higher density developments. The problem? Opponents persist in shouting them down.

Addressing such resistance has more to do with leadership, education and communication than with prices of materials and labor.

Some incremental approaches deserve consideration. Infill development could create additional housing at a lower cost. In many cities, 30% or more land within their boundaries is vacant. Some is developable. Some is not. Many vacant lots could provide useful housing but can’t be developed properly within the current code requirements. Something like an Infill-Planned Development (PD) might allow creative uses of vacant lots in a profitable manner.

Likewise, there are functionally obsolete developments within cities that might serve as housing with some creativity. One city in our state is dealing with a situation in which developments built for the tourist trade have seen such demand disappear. At the same time, the demand for affordable housing has increased. Converting the uses to meet regulations would be a daunting task. Might something like a Conversion-PD address the issue?

One aspect of zoning in our state deserves attention. Minimum lot sizes and setback requirements harken back to the day when land was plentiful, and infrastructure costs were much lower. Allowing the market, rather than the zoning code, to set these, within the bounds of health and safety, would be a welcome move.

As mentioned earlier, addressing the problems regarding the lack of affordable housing will require leadership. Municipal leaders must accept its importance. Other leaders and entities should as well. For example, when service workers cannot find affordable housing in their city of employment, this places additional burdens on overstressed highway systems. No city is an island.

The issue of housing is broad and complex. It is as much a human concern as an economic one. Shelter is an essential one in terms of human motivation.

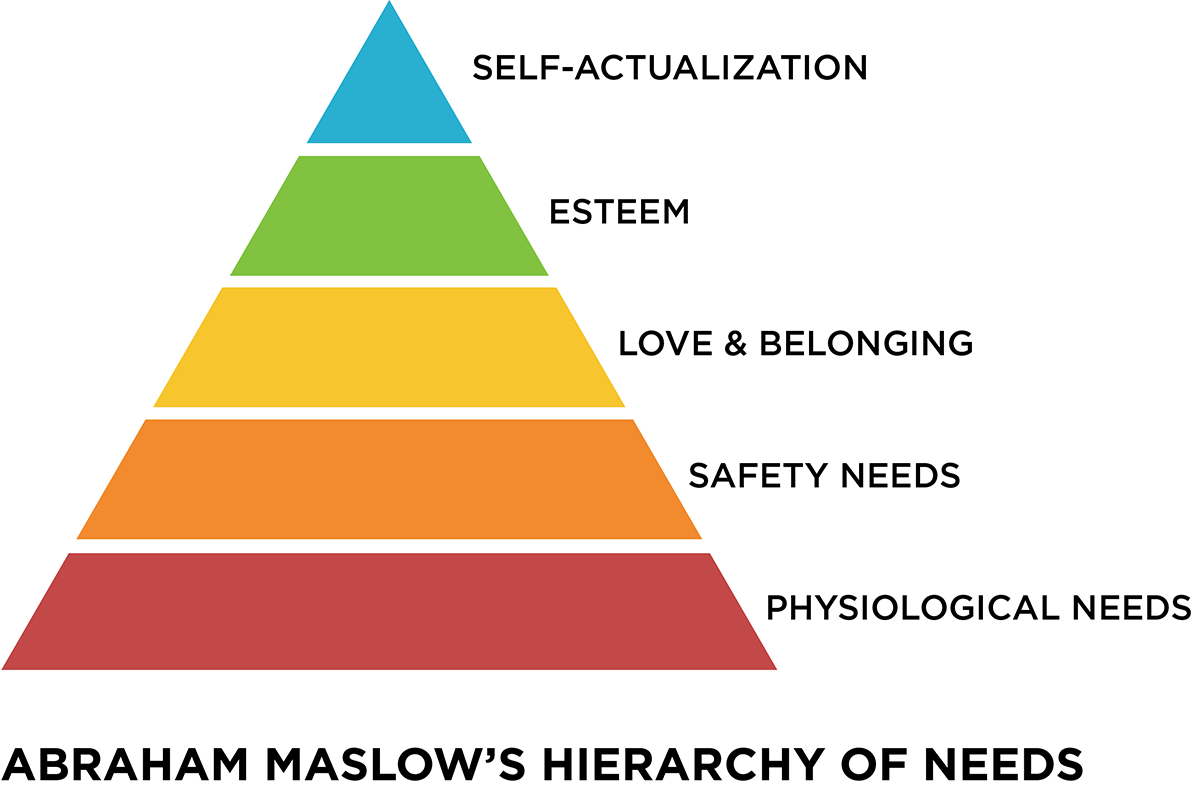

In a 1940s study, American psychologist Abraham Maslow developed a theory of human motivation he termed “a hierarchy of needs.” This means that humans find motivation at specific levels, like the layers of a pyramid. Individuals must have fully met their needs at one level within the pyramid before becoming motivated to achieve the needs of the next level up. Put more bluntly, an individual who is struggling to put a roof over his head will focus on that before exploring his true calling in life. An empty stomach does not motivate a brain to seek compliance with social norms, much less prestige.

At the most basic level, our physiological needs include our bodily requirements, including the basics of shelter. If we lack any of these needs, we need to fulfill them before we can motivate ourselves to pursue other needs.

Thus, if we wish our citizens to find the motivation to become useful, productive and involved, they must first have shelter, food, water, and sleep. Hardly anyone would suggest depriving others of one or more of the latter three. We regard them as essential to the good of all. This leaves shelter as the unmet need.

What this means is that we shall never solve the problem of housing affordability until we decide that housing is a human right, one not decided by profit but by compassion and good government.