And so it goes. In the case of making a vital decision about planning and land-use matters, planning commissions and elected officials can face a situation in which that decision will please and infuriate in equal measures. In other words, it is neither easy nor pleasurable.

Consider decision making. There has not been a better time in recent years to pay close attention to the urban planning function of public administration. Legislative attention at the state level has made it particularly important. This justifies a close look.

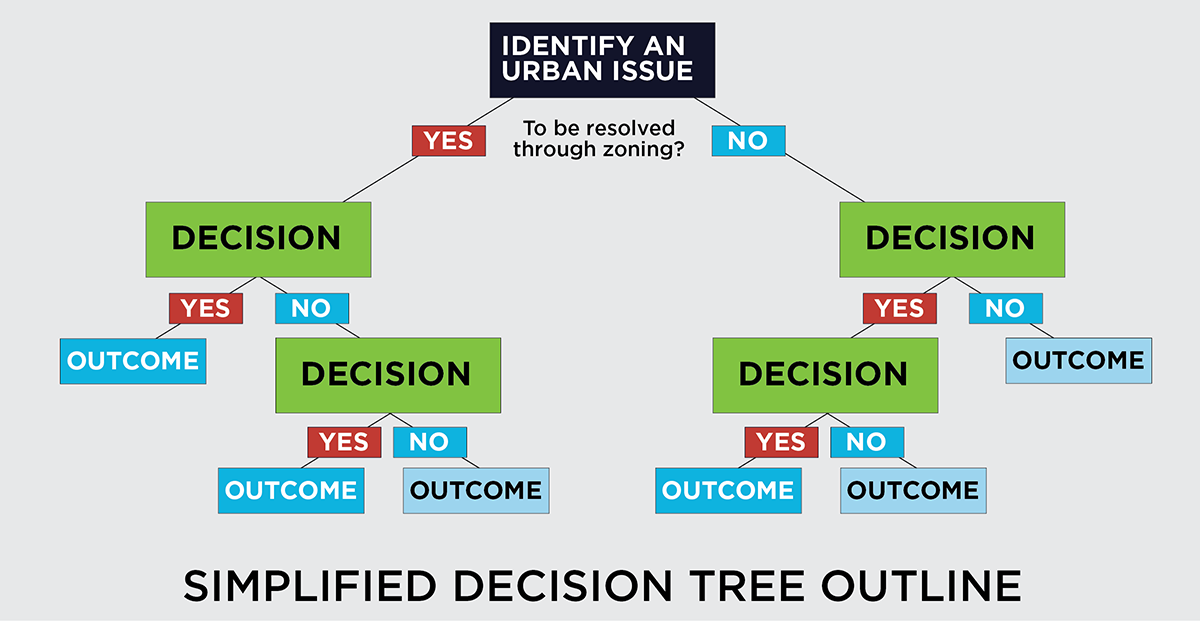

A “decision tree” provides one method of making decisions. This tool evaluates different courses of action based on possible outcomes and their associated risks. It includes a visual tool: a tree with nodes and branches. A benefit is that it allows small or incremental decisions in making a larger one.

Let’s look at two examples, one for small cities and one for the larger ones.

At the small city level, one might ask, after analysis, do we have a major issue in our community, say the random location of unregulated factory-built housing?

A “yes” answer would lead to another branch in which a second question is asked: Is this an issue that land-use regulations could address?

Again, a “yes” answer would lead to another branch with another question: Does our city have an active and responsible planning commission with up-to-date plans and regulatory documents?

At this point, the branches may split. If the answer is “no,” then does our city have the capacity to form a planning commission composed of at least five members who would meet at least quarterly and address complicated land-use decisions, including the one in question?

Here, for small communities, a “yes” answer would lead to another branch. A “no” might lead to the question, is our city council willing to take on this responsibility?

Consistently negative answers could end this tree. The city needs to examine another method of dealing with the issue.

For larger cities, the tree is more complicated but equally useful. Let’s take a shortage of workforce housing as an example. After the issue is identified, a first question should be, was this issue identified and documented in an adopted plan?

A “yes” leads us further. A “no” returns us to the planning process.

Proceeding, we then ask, is this an issue that land-use regulations might address?

Here is where it gets scary.

Assuming the answer is “yes,” the next question might be, do we have a possible solution that is legally permissible?

It is seductive to assume that a “yes” would end the tree. An experienced decision maker would, however, insert another question: Will our citizens allow us to implement that solution?

Here is where making valid decisions affecting our community seems similar to walking through a minefield. Inexperienced observers and “out-of-state consultants” operate under the underlying and unsupported assumption that the public officials who develop and implement regulations can always make rational decisions.

It is pleasant to think so. It is also unrealistic. Few decisions can develop on a completely rational basis.

American scholar Herbert A. Simon, in a classic work on decision making, formed the term “bounded rationality.” This concept states that “objective rationality” is not always realistic due to limits existing in the real world. These limits can include the following:

There is limited knowledge of workable alternatives. As Zhoudan Xie, a senior policy analyst at George Washington University, pointed out in her 2019 article “Bounded rationality in the rulemaking process,” “[Regulators] may have greater expertise, experience, and data than many other people, but they are still humans rather than robots.” One workable alternative often eludes decision makers in their analysis. That is the “do-nothing” choice. At the other end of the spectrum are complicated decisions that require massive expenditures of money and staff time for enforcement.

There is an incomplete knowledge of possible consequences. The pervasive “law of unintended consequences” has soured the public on many heralded decisions. For example, one of the most often stated issues for a community is, “Our town needs a bypass for the automobile traffic.” The next issue often stated is, “The older parts of town are deteriorating since all the businesses have moved to the bypass.”

There are limits to assessing the costs versus the benefits of alternative solutions. Unrealistic assumptions and unreliable data loom like medieval harpies over seemingly wondrous decisions. Just ask an urban planner who remembers downtown malls or urban renewal, aka “urban removal.”

What are we to do? Let us return to Simon’s works. He also developed another term once popular in public administration: the concept of “satisficing” behavior. This simply means achieving acceptable objectives while minimizing complications and risks. In other words, “Don’t overthink it.” As with the old analogy of dipping beans from a barrel, the last few steps of any job may cost more effort and time than all the previous steps combined.

Or, as a famous mayor in the lower half of our state (LA) once observed, “We fall into the mistaken belief that if a little bit will do good, then a whole lot will cure. And it ain’t always so.”

With that in mind, let’s return to the decision tree. Assuming we have an idea the general public will allow, can it be addressed without regulations? If no, we turn to regulation. Then, is a proposed idea the least intrusive one possible? If so, are there potential backlashes, i.e., unintended consequences, looming?

See where this leads us? Now let us think of our community. Let’s zero in on one of the most pleasant and popular areas of our city. Then let us answer, truthfully, one simple question: Was this pleasant place achieved through intensive regulations or did it develop because of no, or few, regulatory restraints?

In one of the author’s several adopted hometowns, Little Rock, the Hillcrest neighborhood answers that question quite eloquently.

In meetings where experiences in urban planning lead the discussion, we often hear statements like “What we did was…” or “We were able to get the following passed” or “We talked the board or council into….”

Another common comment was, “It was consistent with the plan, there were no apparent problems, and the staff recommended approval without exceptions. What happened? Some neighbors shouted it down with vague references to the type people it might attract.”

What if a planning proposal is not presented as a victory regarding an issue but as a rational approach to achieving positive community development? Second, what if the approach was so consistent with adopted plans and engineering analysis, and sound urban planning principles that it should create “by-right” land uses? Third, what if regulations provide that such land uses will avoid veto by a group of neighbors who did not employ a rational consideration of actual facts?

In reality, public administration is not a win/lose affair. It is a process of using governance to promote the health, safety and welfare of the community. Tools like decision-tree analysis could help.